Reserve Funds 101

Towns decide to create reserve funds for several reasons, including to ensure specific funds are available for a specific purpose when that need arises, to provide the selectboard with flexibility in spending, and – perhaps most importantly – to prepare a town for the unexpected.

Municipal budgeting is complex and more of an art than a science; towns can face financial hurdles that are unexpected and unpredictable. Natural disasters such as floods and pandemics come to mind. To help manage financial uncertainty, it is wise to save for a rainy day. Most municipal financial experts agree that a municipality should maintain financial reserves of at least 15% percent of annual operating expenditures. The more unstable a municipality’s revenue base, the more funds it should hold in reserve. However, VT law doesn’t explicitly authorize carrying forward any “rainy day” funds (i.e. a sum of money set aside to address revenue shortfalls or unexpected costs) or unencumbered fund balances. The general rule of budgeting in Vermont law is that money not spent in a budget year must be re-appropriated by the voters for the following year as part of the budget approval process at town meeting. Creating a reserve fund is the only legally recognized method in Vermont to provide a cushion for a town to account for unanticipated cost overruns for the year.

Reserve funds are established by the voters at a duly warned special or annual town meeting for the purpose of funding a specific public item or project. A reserve fund can be set up to act as a “rainy day” fund to address temporary unforeseen revenue shortfalls and/or unpredicted expenditures that would otherwise require a town to borrow money, go back to the voters and send out a supplemental tax bill, or reduce its level of town services. So, instead of padding the budget with a penny on the tax rate (which is not permitted by law) or borrowing from legally restricted funds, the law gives towns this mechanism for addressing these shortfalls.

Don’t confuse “reserve funds” with “dedicated” or “designated” funds. A “dedicated” or “designated” fund is money that is set aside by the selectboard in the budget for some specific purpose, but without any legal basis or strings attached. Unlike with a “reserve fund,” the selectboard may spend dedicated or designated funds for another purpose if the need or desire arises within the limits of their existing discretionary budget authority.

The key elements of a reserve fund are 1) the fund’s creation, 2) the name and purpose of a fund, and 3) the method of appropriating money to the fund. A single article or two articles can be used to create the reserve fund and appropriate money to it. We have developed a Model Town Meeting Articles resource to guide you, which can be found under the “Resources” heading at the bottom of the webpage. While the reserve fund itself will continue to exist until rescinded by the voters, any funding mechanism that is approved is only in effect for the ensuing year.

Once a reserve fund is established by the voters under 24 V.S.A. §2804(a), the selectboard can only spend money in it for the purpose(s) for which the reserve fund was established.

The main limitation on a reserve fund is voter authorization. Once created, selectboards can use reserve funds at their discretion – without further voter approval – for the town-related purpose that the voters authorized it for, and nothing else. However, its lone limitation happens to also be its greatest flexibility: the selectboard can always go back to the voters (at an annual or special town meeting) to get their approval to use it for something other than its original purpose.

Because the law places a reserve fund under the control and direction of the selectboard, it would be wise for the selectboard to adopt a policy for administering the fund. A policy will guide its decisions about how money will be set aside in the reserve fund, the circumstances under which reserve funds will be spent, and how to build back its reserves. Selectboards looking for a place to start can use our Model Reserve Fund Policy with Guidance resource listed last under the “Documents” heading.

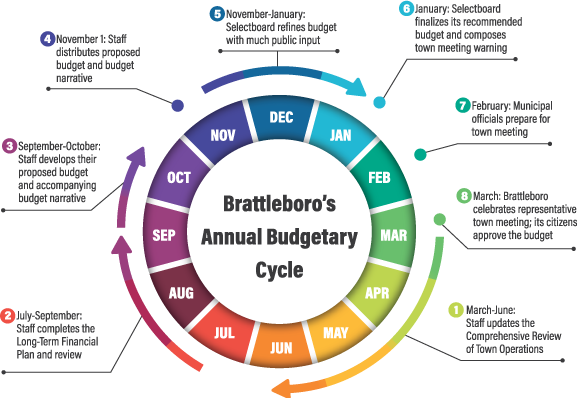

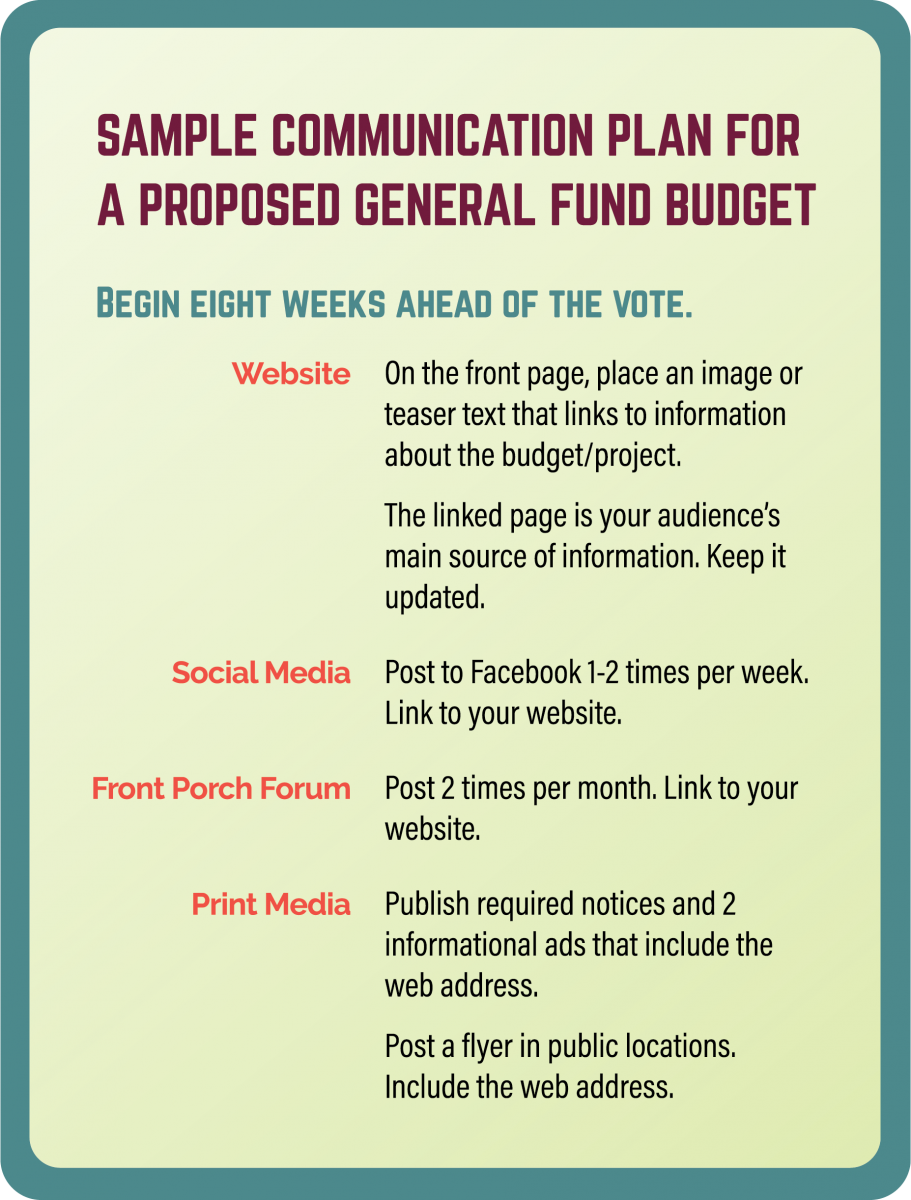

els and phases. Let’s walk through preparing for town meeting and informing your community about the proposed budget.

els and phases. Let’s walk through preparing for town meeting and informing your community about the proposed budget.